Statistics is a Scientific Instrument

The problem is that many people treat statistics as a kind of oracle

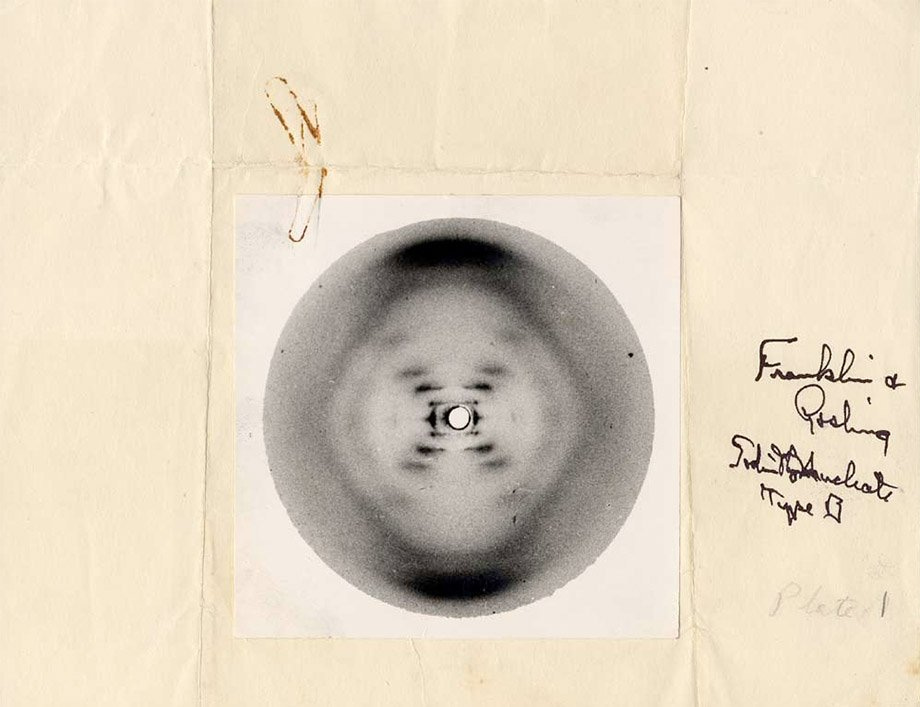

In many ways, the history of science is a history of instruments giving us new ways of observing the world and subsequently noticing phenomena we couldn’t previously. (And then eventually mastering some of those phenomena and using them to create new instruments!) Telescopes let us observe cosmic phenomena and microscopes first let us see things that were too small for the naked eye. Galvanometers, Hall probes, and oscilloscopes open the world of electromagnetism while geiger counters and bubble chambers start to unmask radiation and subatomic physics.

Statistics is also an instrument. The sooner we embrace that fact, the sooner we can fix many of the most publicly prominent problems with science.

We don’t often think about statistics as being in the same category as a microscope. But if you think about it, it’s a tool (built with math rather than physical engineering) that enables us to observe phenomena in the world that are invisible with the naked eye. John Snow used it to observe sewage causing cholera. Jonas Salk used it to show that the polio vaccine worked. Many fields that use statistics as one of their main instruments: epidemiology, medicine, and most of the social sciences.

Statistics is a powerful instrument, but like any instrument, it provides evidence that then needs interpretation to infer what’s going on with the underlying phenomena – it doesn’t generate truth directly. Look at the X-ray crystallography image of DNA: it’s nowhere near obvious that you’re looking at a double helix. Statistics is the same. The problem is that many people – both practitioners using the tool and people listening to them – treat it as some kind of oracle. Don’t take it from us – the fathers of statistical testing themselves flagged the limits of statistical inference:

From my point of view, the tests are used to ascertain whether a reasonable graduation curve has been achieved, not to assert whether one or another hypothesis is true or false

Karl’s son Egon Pearson:

We were very far from suggesting that statistical methods should force an irreversible acceptance procedure upon the experimenter. Indeed, from the start we shared Professor Fisher’s view that in scientific enquiry, a statistical test is “a means of learning”, for we remark: “the tests themselves give no final verdict, but as tools help the worker who is using them to form his final decision

When decision is needed it is the business of inductive inference to evaluate the nature and extent of the uncertainty with which the decision is encumbered. Decision itself must properly be referred to a set of motives, the strength or weakness of which should have had no influence whatever on any estimate of probability.

Many contemporary science problems, from the replication crisis to pick-your-politically-charged-science-adjacent-debate are downstream of the failure to treat statistics as just another instrument.

If we were to treat statistics as an instrument, what would we do differently? Perhaps we’d have more statisticians working closely with other disciplines to create methods that are both tuned for that discipline and hook into other instruments. This could look like a kind of biomedical Kalman filter that sits on top of simulations and iteratively integrates data as it comes in. And at the end of the day, the most straightforward way to treat statistics as an instrument and not an oracle is to insist that no matter what the statistics “say,” science needs to bottom out in falsifiable predictions.