Publish Incomplete Reports!

Progress in science has often hinged on someone going “huh, that’s funny” without a clear explanation

Progress in science has often hinged on someone going “huh, that’s funny” without a clear explanation. Alexander Fleming noticing a bacterial dead zone on a culture; Penzias & Wilson being unable to avoid a noise pattern from their radio telescope; Wilhelm Röntgen noticing his bones outlined on a wall; Percy Spencer, who created microwave ovens, noticing a mysteriously melted chocolate bar in his pocket; the list goes on. These observations then often take many years to explain in a way that would satisfy a journal editor or peer reviewer.

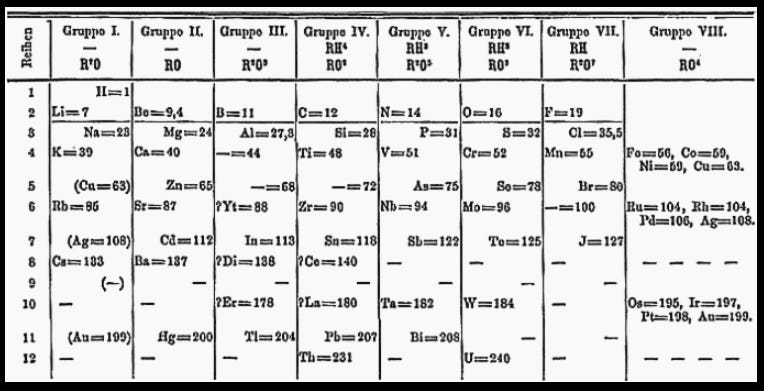

Progress in science has also depended on excellent articulations of open questions and visions: Hilbert’s problems, the gaps in Mendeleev’s periodic table, or Wheeler’s provocations. When done well, this work often spurs the work of hundreds of other scientists over decades or centuries.

In other words, incomplete stories are critical to science.

Good incomplete stories give others a springboard to do their own work from: meticulously collected data without an explanation, a precise vision for a whole program of work, a well-spec’ed engineering bottleneck, an observation of mathematically similar phenomena in very different fields.

But incomplete stories are anathema to how we do science today. Incomplete stories are incompatible with replicability, peer review, and the general attitude that the quanta of science is a paper with a problem statement, a chunk of work, and a conclusion. This incompatibility leads to situations where researchers contort or add terrible explanations and experiments to something that just wants to be “hey I saw this weird thing or did this cool thing.” Or they just sit on an incomplete story for years. Or forever. All of this makes science worse.